Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb.

Fabaceae/Mimosaceae GUANACASTE

Uncommon evergreen or briefly deciduous canopy tree (25-35 m) known for its superlative proportions, its expansive, often spherical crown, and its curiously shaped seed pods. The abundance of this tree (especially in the province of Guanacaste where it is prized for the shady relief it provides from the intense sun) coupled with its immensity have made the Guanacaste one of the most widely recognized and appreciated species in Costa Rica – in fact, it is the national tree of this country.

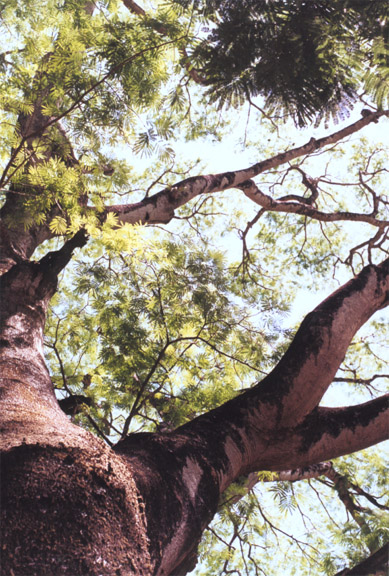

Description: Guanacaste boles are cylindrical and generally straight and columnar, with mature specimens reaching well over one meter in diameter. Unusual in a tree of these proportions, buttresses are completely lacking. The bark is light gray in color and it is textured by prominent, dark, vertical fissures that show a marked reddish-brown color upon close inspection. In young trees, these fissures are closer together and their confluence lends a hallmark, reddish hue to the bark of Guanacaste saplings. Older specimens often present broken, chipped or scared bole surfaces. The height at which branches first occur along the bole – as well as overall tree shape – vary considerably among individuals and are habitat-dependent characteristics. Frequently, Guanacaste trees grow as single specimens in a sunny pasture. Under these conditions, massive, extended, horizontal limbs emerge low on the boles, forming giant, hemispherical, widely spreading crowns. In the forest (where competition for light is intense), trees tend to become taller and branching occurs at a higher level. Tree forms then become somewhat narrower, though crowns are still rounded and hemispherical shapes are maintained by those that have reached the canopy.

The bipinnately compound, alternate leaves (20 cm by 17 cm) are confined to the outer shell of the crown, yet they are plentiful enough to make it moderately dense and green. The tiny leaflets (8 mm by 2 mm) number about 36 pairs to a pinna and there are 11 pairs of pinna per leaf. Near its base, the twiggy petiole bares a small, raised, oval gland. Most foliage is shed in December, at the start of the dry season, and trees remain very nearly leafless for the following two months. In late February, a growth surge is initiated that re-establishes a fresh, thick crown by April.

Concurrent with crown renewal is the appearance of globular flowers (3 cm) in the axils of the new leaves. Supported by a long pedestal (4 cm), each spherical white head – composed of about fifty individual flowers – sports thousands of thin, filamentous stamens as its major feature. The blossoms themselves each consist of about twenty stamens and a single pistil, bound together at the base by a short, green, tubular corolla and an even shorter calyx. Guanacaste flowers are very fragrant and during intense flowering periods their odor permeates the air for many meters in all directions. In Manuel Antonio, flowering lasts from late February to early April. Surprisingly, no fruiting activity immediately follows the decline of the blossoms. Rather, nine or ten months pass before small, green pods first appear high in the crown (December). They reach full size by February and finally begin to harvest in March – a full year after flowering ceased.

Guanacaste fruits are large (10 cm), spirally organized pods that resemble orbicular disks. (Their shape suggests the usual Mimosaceae fruit – a long, narrow, flattened pod – taken and wound around an axis perpendicular to its plane.) Made of thick, soft tissue with a leathery feel, the glossy brown pods contain about twenty, radially arranged seeds. Guanacaste seeds (1.5 cm) are brown and marked with a conspicuous light brown or orange ring. They are also very hard – resembling small stones rather than tree seeds in their strength and durability. In order for germination to occur, the hard seed coat must be broken to enable water to reach the embryo. Otherwise, they will lie dormant indefinitely. Fruit harvests last from March to April, as the green pods turn brown in the Guanacaste crown and are slowly shed. Vigorous trees will produce large crops on a nearly-annual basis. In June, Guanacaste seedlings can already be seen, germinating in the moist soil of the early rainy season.

Similar Species: Ardillo (Cojoba arborea) and Iguano (Dilodendron costaricense) possess similar, bipinnate leaves with extra-fine leaflets. Though of equally impressive stature, these two trees can be distinguished readily from Guanacaste. Ardillo has tan-colored, heavily wrinkled and rough bark – nothing like Guanacaste’s unmistakably gray, and vertically cracked cortex. Iguano’s leaflets are serrate (an unusual feature in a bipinnate tree), while those of the Guanacaste are entire.

Natural History: Guanacaste trees appear to delay the onset of fruit development – some nine months – so that seed maturation will coincide with the start of the rainy season. This adaptive behavior presumably is designed to give germinating seedlings as much time as possible to establish root systems before the start of the next dry season. Both Guapinol (Hymenaea courbaril) and Cenizaro (Samanea saman) exhibit similar reproductive strategies. Of course, Guanacaste trees – like all deciduous and semi-deciduous species in this part of the world – share in the water conserving benefits of dry season leaflessness.

Guanacaste flowers are heavily visited by bees – insects that probably are responsible for pollination as well. Guanacaste seed pods, however, are completely ignored by native fauna – and they accumulate on the forest floor underneath parent trees. Perhaps, as Janzen and Martin (1982) theorize, Guanacaste pods were among the foods exploited by certain Neotropical megafaunal species that became extinct some 10,000 years ago (e.g. giant ground sloths, giant bison). Under this scenario, the tree remains today without an effective see-dispersing vector (see introduction).

As mentioned in the text, tough-coated Guanacaste seeds do not begin to grow unless their protective covers are punctured in some way. This may be an adaptation designed to keep the seeds from germinating while still in the pods at the start of the rainy season – and very likely still underneath the parent tree after having fallen from its crown. With more time to find them, foraging ground sloths (and other extinct mammals) could eat the pods and transport the seeds to a new site. The resulting mastication and digestion of the fruits would induce the scaring necessary to provoke seed germination.

An insect plague, common to Guanacaste trees of the Central Valley, produces spherical green galls (1.5 cm) on new shoots in February and March. Allen (1956) indicates that similar parasitism occurs to Guanacaste trees of the wet, southwestern lowlands (around Palmar Sur).

In El Salvador, Enterolobium is known by the common name “Conacaste” – a word of indigenous Nahuatal origin and meaning “Ear Tree” (Witsberger, 1982).

Uses: The Guanacaste is among the most majestic and esthetically pleasing of Costa Rican tree species. Tolerant of a wide range of rainfall levels, temperatures and soil conditions, they can thrive in most low-elevation, tropical habitats. Guanacaste trees are highly valued as ornamentals and the shade they provide creates many an oasis on the searing and sun-baked Guanacaste plain.

Healthy Guanacaste trees generate massive, nearly annual crops of seeds. With care, these seeds can demonstrate germination rates of nearly 100%. Guanacaste seedlings then grow rapidly, often reaching over one meter in height in their first year of life. These aggressive reproductive characteristics could be beneficially exploited in reforestation projects.

According to Allen (1956), Guanacaste wood is reddish-brown of fine quality and it is prized in the construction of furniture.

Distribution: Guanacaste trees are probably limited naturally to the dry tropical forests typical of the Guanacaste region of Costa Rica. They have been planted further south and individual trees often thrive in this, more humid, environment. Guanacaste ranges from Mexico to northern South America.

Photos: Tree Tree2 Tree3 Tree4 Trunk Leaf Leaf2 Leaf&Flower Flower Fruit Fruit2 Fruit3